Emergency Calls in Finland

The U.S. and Canada have implemented 9-1-1 as their unique emergency services number. Worldwide, there are more than 170 different numbers — not all of which are three-digit numbers — in operation to get support from first responder organizations. In the January issue, I began a series highlighting some, hopefully, interesting information on different countries worldwide and their emergency number situation. As follow-up to discussing the complicated system of eight emergency numbers in Austria, as well as providing an overview of the 112 emergency number used in Europe, I will focus on another European Union (EU) country: Finland.

Finland is famous for being home to a company that started by producing rubber boots and car tires and is today a leader in cell phone production, and for its use of the Finnish sauna. Almost every business building in the country has a wooden sauna cabin adjacent to a meeting room(s), allowing executives to continue a business meeting at a dry heat temperature of approximately 90° C (190° F). And this is done regularly. Many high-level decisions have been made by nude and sweating business people in a sauna.

Demographics

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region in Northern Europe, which includes Norway, Sweden and Finland. The area is geologically more than 3 billion years old. Finland is bordered by Sweden on the west, Norway on the north and Russia on the east. To the south is the Gulf of Finland.

Around 5.4 million people reside in the country, with the majority concentrated in the South. With an area of 338,424 sq. km (130,596 sq. miles), Finland is a little smaller than Montana and the most sparsely populated country in the EU. The capitol and largest city in Finland is Helsinki (in the Swedish language it is called Helsingfors), located in the very south of the country, with a population of almost 600,000. The official state languages are Finnish and Swedish, and Sami is a recognized regional language.

After a long history as part of Sweden, Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire in 1809. The Finnish Declaration of Independence from Russia was signed in 1917. (A Finnish friend of mine with a very dry sense of humor has his own interpretation of this historic moment, saying, “And in 1917, Finland gave Russia its independency back.”)

Later in the first half of the 20th century, a civil war and wars against the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany occurred, followed by a period of official neutrality during the Cold War. Finland joined the United Nations in 1955 and the EU in 1995.

Finland’s currency is the Euro (€). The country is in the Eastern European time zone (UTC+2 hours), which is six hours ahead of Washington, D.C.

Emergency Response Centres

Finland had different numbers for its different emergency services for a long time. But with the implementation of the European emergency number (“112”) in 1992, a transition to get rid of these legacy numbers began and will be completed in early 2011 with the closing of the last remaining number, “10022,” which is the old emergency number for police.

With that, 112 will be the only remaining emergency number on the mainland of Finland. There will be only one separate quasi-emergency number for marine rescue/open sea operations (“0204-1000”). Any relevant 112 calls will be transferred to the national marine rescue centre.

To deal with 112 emergency calls, Finland has established the Emergency Response Centre Administration, which is a public authority financed by the nation’s budget and steered by the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

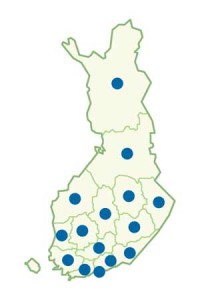

The emergency calls are received by 15 emergency response centres (ERCs) spread all over the country (see Figure 1). Most of the centres are located in southern Finland due to the low population density in the northern part of the country and therefore fewer emergency calls. The ERCs are all equipped with the same technology for calltaking, computer-aided dispatch (CAD) and radio dispatch.

In the late 1990s, Finland was the first European country to install a unique and harmonized digital radio network for all public safety organizations in the country. Therefore each ERC can receive calls from another region and dispatch respective first responders in the region the call originates from.

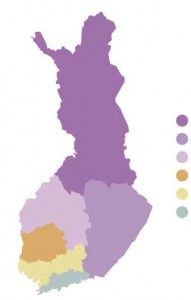

Figure 2: Map of Emergency Response Centre Consolidation – Dark Purple: Northern Finland and Lapland; Medium Purple: Ostrobothnia and Central Finland; Light Purple: Pirkanmaa and Satakunta; Orange: South-West Finland and Hame; Yellow: Uusimaa; and Blue Grey: East and South-East Finland. (Illustration Amane Kaneko)

Due to financial and staffing problems, the ERC Administration is restructuring the centres over the next five years. The plan is to reduce the number of ERCs from 15 to six (see Figure 2). This change provides the opportunity to have fewer, but more highly qualified personnel; there will be less equipment to purchase; and, therefore, overall investment and operational costs will be reduced.

Personnel & Call Volume

Today, 538 civilian operators — in the function of calltaker, dispatcher or task supporter/monitor — are managing the emergency calls. They receive 4.2 million calls annually, of which 3 million are emergency calls, 37,000 are alarm system calls and 1.114 million are other inquiries, such as non-urgent ambulance service requests.

Out of the 3 million emergency calls, 750,000 calls are made unintentionally and 130,000 are inappropriate or malicious calls. To reduce these, the Finnish government introduced a new emergency telecommunications act that will enable the use of a 15-second voice recording designed to limit the number of calls made from cell phones without a SIM (subscriber identification module) card. The voice recording tells the caller that they have reached emergency services and should not continue if making an inappropriate or malicious call, otherwise they will be fined.

Across the nation, 91% of all emergency calls are answered within 10 seconds and 96% within 30 seconds.

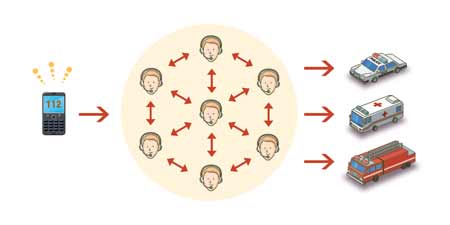

Emergency calls result in a dispatch of first responder forces. Calltakers initiate tasks and give them directly to field units via the nationwide digital radio system, whereas task supporting and task monitoring is separate in the majority of ERCs (see Figure 3, below).

In Finland, 7,500 government police officers, and 3,000 professional and 20,000 volunteer firefighters under municipality leadership are active. Firefighters also handle EMS, but there are more than 1,000 private EMS providers outside the fire brigades.

Multilingual Service

The ERCs offer multilingual services for emergency calls. Swedish and English are dealt with by multilingual calltakers in the ERCs. Additional languages, especially Russian, are handled via conference calls with a professional translating service.

Access for People with Special Needs

Although the requirements for new solutions to serve people with special needs, such as speaking or hearing disabilities, have been identified, at the moment there is no procedure for silent calls. A workgroup, 112-SMS (texting to emergency), has recently finished its work, but the results have not yet been implemented.

For the time being, every ERC offers an additional separate phone number to receive short message service (SMS) or text messages. Because the message isn’t coming in through the 112 emergency number, the usual quality of service — especially its priority level through the operator’s networks in times of network congestion or the call quality in the ERC — cannot be guaranteed.

Caller Location

The location of the caller is available for the calltaker by the click of a button in the CAD system, which initiates an automatic transfer of the location.

For landline phones, the result is the address of the phone’s owner. For cell phones, the location is determined by the position of the cell network’s base station. The accuracy depends on the density of base stations, which gives better results in the southern part of the country than in the north, where cell base stations cover larger areas.

Currently, cell phone users with foreign subscriptions cannot be located. The ERC Administration has started working with the network operators on a solution to offer the same quality of service to business or leisure travelers.

Citizens’ Feedback

The ERC Administration has established a system for receiving feedback from citizens to gather information about their satisfaction with the services. People can send feedback about the 112 services via the ERC Administration’s Web site (www.112.fi). All input and all complaints are investigated, and the citizen receives a professional answer about the investigation’s results. This is possible because all calls are recorded, stored and available for investigation for a period of five years.

The ERC Administration measures the satisfaction of its customers annually. The latest results for 112 calltaking were 4.38 (one is the worst and five is the best result), and 3.43 for emergency services, which is accepted as good.

Projects & Reforms

The Finnish ERCs are at the starting point of a large-scale organizational reform that is scheduled to be completed at the end of 2015. The major parts of this reorganization include the new emergency telecommunications act, new networked software and a common database for all ERCs to improve the service to the population and allow communications overflow between the ERCs, and finally the reduction from 15 to six ERCs across the country. These are big challenges for the best of Finland and its population.

Next Issue

After two articles about European countries (Austria in January 2011 PSC and, now, Finland), my next article will give you a glimpse of emergency services in Australia. Keep reading.

About the Author

Brigadier-General Manfred Blaha is technology advisor for national crisis and disaster prevention management for the Ministry of the Interior in Austria. As a telecommunications expert, he leads several projects for Austrian Federal Police Communications (112+ Dispatch Centres, Radio Network, Emergency Operations Centre, Civil Protection Communications). He has been an APCO International member since 1996, served as APCO’s international vice president from 2005–2007 and has been the International Chapter representative on the Executive Council since 2008.

Originally published in Public Safety Communications magazine, Vol. 77(2):34-36, February 2011.