Engulfed in an Instant

By Bruce Nedelka, NREMT-P, & A.J. Heightman, MPA, EMT-P

On April 6, 2012, a U.S. Navy F/A-18 jet with a student pilot and trainer on board crashed into a Virginia Beach, Va., neighborhood. Photo courtesy Jon Kight.

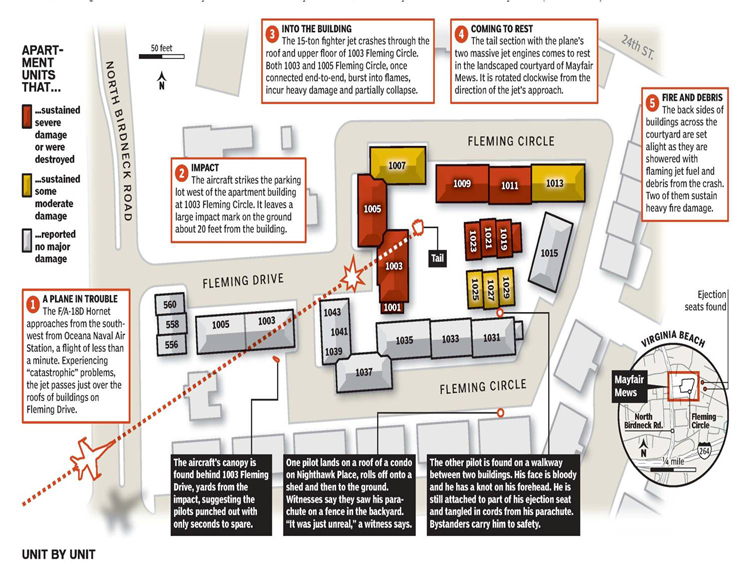

The calm afternoon and the lives of those living in the retirement community of Mayfair Mews in Virginia Beach were forever changed just after noon on April 6. It was at that moment when a U.S. Navy F/A-18 jet with a student pilot and trainer on board experienced serious engine failure from nearby Naval Air Station (NAS) Oceana and plunged to the ground, crash landing into the buildings and courtyard of an apartment complex. Instantly, several buildings were engulfed in flames fed by jet fuel. The dark black plumes of thick smoke could be seen miles away.

About VBEMS

Virginia Beach, Va., is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Virginia and ranked No. 41 in the 2011 JEMS survey of the top 200 cities in the U.S. Its 310 square miles and 38 miles of shoreline is home to approximately 450,000 residents and more than a million daily guests during the summer resort season. The city is also home to several large corporations, including STIHL Inc. and LifeNET Health, and it’s the heart of a large military population in America, with Little Creek, Fort Story, Dam Neck, Naval Station Norfolk and Oceana bases.

Virginia Beach Department of Emergency Medical Services (VBEMS) is a third-service volunteer-based department with more than 1,100 volunteer members staffing the city’s 10 volunteer rescue squads, plus 28 full-time paramedics and four full-time brigade chief field supervisors to augment the volunteers.

The department responded to approximately 39,000 calls for service in 2011. In addition to emergency care and ambulance transportation, VBEMS also operates an all-volunteer Marine rescue team, heavy rescue service, two mass casualty incident (MCI) vehicles, an all-volunteer search and rescue unit, and bike teams. VBEMS also supplies the paramedics for the Virginia Beach special weapons and tactics team and air medical unit; manages post-disaster, medically friendly shelters; and provides lifeguard service for the city’s Sandbridge and Little Island Park beaches. The city doesn’t own any ambulances; all 35 of the VBEMS ambulances and support vehicles are purchased and operated by the 10 volunteer rescue squads. The rescue station buildings are in some cases solely owned by a volunteer rescue squad. In most cases, they’re a city-owned facility housing fire department and EMS resources together.

The Incident

The pager tones that sounded for the incident were just like the ones that had dispatched thousands of calls before. However, this alert announced a call that would test the Virginia Beach EMS, fire and police departments, dispatch center and the city’s entire Emergency Response System like they’d never been tested before.

The Emergency Communications and Citizens Services Department 9-1-1 Center initially received a frantic cell phone call telling them about the crash and the fire. Almost instantly, the inbound queue was flooded with 80 calls. (Listen to some of the calls on the jems.com website.)

This number quickly escalated to 200. At the time of the initial call, 13 staffed ambulances, five staffed paramedic rapid response zone cars, one EMS duty supervisor (EMS-5) and two assistants (EMS-6 and 7) were on duty. However, within an hour, more than 170 volunteers were involved and 30 ambulances were staffed.

During the first 90 minutes of the crash, more than 20 other 9-1-1 calls for ambulances were dispatched. These included a motor vehicle crash with entrapment, and several serious medical cases. Although the turnout of EMS volunteers was so great that none of the cases for ambulances in Virginia Beach required mutual aid, surrounding cities sent fire apparatus to backfill fire stations.

Because of the heavy volume of calls received by 9-1-1, EMS Chief Bruce Edwards assigned an EMS division chief to the 9-1-1 center to assist in triaging calls and refining automatic response matrices and managing the EMS field resources. This was a helpful function because of the increased 9-1-1 call volume and communications.

Some callers gave conflicting information regarding the location and what was unfolding. Some were more precise. All, however, were desperate for help. Cathy Fowler, a 24-year veteran Virginia Beach dispatcher, was on the EMS console that day. “When it became clear that we had a major incident, we all got so focused on our jobs that the 9-1-1 center had an amazing calmness. There was no idle talk; we all did what we have been trained to do,” Fowler says.

The first inbound call entered the system at 12:06:07 p.m. The initial simulcast dispatch was announced to EMS and fire units at 12:07:28 p.m. Although the dispatcher’s voice was calm, the message was clear: There was a confirmed plane crash.

The initial assignment included the duty district chief, Battalion 1; Engines 11, 8 and 3; Navy engine 31; Ladder 11; Ladder 8; Safety 1; and Fire Squad 3.

The EMS units dispatched were EMS-5 (duty field chief); EMS-3 (duty division chief); ambulances 1420, 1425 and 827; MCI-2; and rapid response medic zones 14 and 08. Virginia Beach public safety radio communications is all digital with multiple frequencies and banks. EMS and fire are separate departments, and each has its own primary dispatch channel and dispatchers.

Calls are often “simulcasted” over both EMS and fire channels, by either dispatcher, to announce co-response calls. Doing so serves several purposes, such as giving the same dispatch information about the location and the same incident nature to all units. Units then acknowledge the dispatcher via radio or on mobile data terminal (MDT) and respond to the call.

Radio traffic and communications on the primary and tactical channels in the early minutes could have become uncontrollably chaotic with such a large response. However, primary channel radio traffic was controlled. This can be attributed to several key factors:

First, the dispatcher’s voice was not frenzied. Had he sounded excited, field providers could have picked up on that emotion, and each individual’s adrenaline rush could have escalated;

Second, fire department and EMS personnel had been involved in numerous training exercises and drills to prepare them to handle this type of situation. During the years, more cooperative, multijurisdictional drills between VBEMS, Virginia Beach Fire Department (VBFD), military fire and EMS, Norfolk International Airport, and local hospitals, plus many large outdoor events in the city’s resort areas, proved to be invaluable rehearsals for this incident. It made the development of on-scene unified incident command much smoother and familiar.

Although the first 9-1-1 call was still being received, Virginia Beach police officers near the crash site advised dispatcher Tonya King that they heard the thunderous crash and could see the smoke.

King says, “My first thought was that what I was being told on the radio couldn’t be real. But when I looked at my computer screen and saw 9-1-1 calls flooding in, I knew this was truly the real thing.”

Response Activates

Within the first hour, the staff of 13 dispatchers increased to 34 as their preplanned emergency response team was activated, calling in off-duty dispatchers and supervisors. The additional personnel enabled multiple command and tactical channels to be staffed and allowed several personnel to make the required return calls to hundreds of 9-1-1 hang-ups.

Close behind that officer were two other EMS members, one of which was an off-duty EMS volunteer Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) medic and the other was Jay Leach, an EMS Volunteer Brigade Chief who was an on-duty paramedic (Zone-14) at the time and was part of the initial dispatch assignment. Both were near Laskin Road and Birdneck Road when the crash occurred.

Citizens joined forces with emergency responders to work feverishly to get residents out of the buildings, remove the injured and find the pilots. Initial reports indicated that only one pilot and parachute were seen. However, dozens of additional calls came in with unconfirmed and conflicting reports of a second pilot being involved. This led to several minutes of intense searching and confusion: Was there one pilot or were there two?

Police officers and citizens quickly located one pilot and called for an EMS team to treat his injuries. Although a few units and personnel were already staging near 24th Street and Birdneck, access to the pilot was south of Fleming Drive. An incoming ambulance was flagged down by police as they were driving north on Birdneck from the area of Interstate. That ambulance loaded the pilot, advised EMS-5 and continued on to the hospital. Confirmation was then received from citizens and Oceana Air Traffic Control that a second pilot had been on board.

A radio message from Brigade Chief John Fusco, the Duty Shift Commander, advised inbound units to be vigilant in their search for signs of a parachute or pilot as they approached the scene. Crews knew the pilots had been ejected and thought they had a good chance of finding the missing pilot if they located a parachute.

An Unexpected Find

Pat Kavanaugh, a resident of Mayfair Mews and a retired Virginia Beach Volunteer Rescue Squad member, opened his sliding door after the crash to investigate. To his shock and amazement, he found the missing F/A-18 pilot lying on the patio with a parachute hanging on the side of the building. After Kavanaugh reached the pilot’s side, he heard the pilot utter, “I’m sorry I destroyed your home.”

Kavanaugh’s EMS training and experience instinctively kicked in. He conducted a quick patient survey and found no lifethreatening injuries. He then elicited the help of several neighbors and police officers to drag the pilot away from the burning building. An EMS crew was then directed to the location, and the pilot was moved quickly to an awaiting ambulance to be transported to Sentara Virginia Beach General Hospital.

As can be expected with so many calls flooding the 9-1-1 center and nearly 100 citizens and first responders on the scene, some erroneous information came in during the first hour or more. One of the more tense time periods for incident commanders and responding crews came when reports continued that the second pilot was missing.

The Search

It was then known that the two pilots had been ejected as the plane fell to the ground. The fighter jet’s canopy was found behind an undamaged building near the entranceway into the complex. EMS-5 radioed again to incoming units that the second pilot was still missing and that they should include trees, ditches and rooftops in their search. Bystander reports of a pilot being in the burning rubble were proven wrong when the radio cracked that the second pilot was found conscious and alert.

The fire units took up positions according to a fire pre-plan and recommended an immediate second alarm. That was closely followed by a third and then a fourth alarm. Available fire resources were quickly depleted citywide, so mutual aid from three neighboring cities were requested. Specialized crash rescue units from NAS Oceana were dispatched along with one of their engines and ambulances.

Location Details

The Mayfair Mews apartments are located just north of Interstate I-264 at Birdneck Road and Fleming Drive. Northbound traffic on Birdneck Road quickly became jammed. As northbound traffic congestion grew increasingly worse, access by responding emergency vehicles was also slowed. So when EMS-5 arrived, Fusco made a series of quick decisions, including a request for the dispatcher to assign a medical tactical channel and announce that any incoming units must approach from the north—Laskin Road—not from I-264 or south Birdneck Road (see map, p. 39). Laskin Road quickly became a controlled intersection by police and a good access point for emergency vehicles and first responders in private vehicles.

With that problem resolved, emergency units could then travel northbound in the southbound lanes from I-264 to access the scene.

Use of Tactical Channels

The Virginia Beach EMS and fire computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system has eight shared tactical channels. The initial tactical channel assigned to EMS operations was changed twice as the fire department expanded its operations. That led to some radio communications confusion in the first hour or so of the incident. In the after-action meeting, senior EMS command staff decided to consider altering the EMS medical command tactical channel allocation on any future incidents of this magnitude and consider assigning the lesser used, but universally accessible, EMS admin channel as its initial working tactical channel. This pre-planned EMS tactical channel would provide a clear channel for EMS operations and is highly unlikely to be overtaken by expanding fire operations.

EMS day-shift captain Earnie Delp (radio designation EMS-6) arrived on scene and became the incident’s medical branch director. He established a staging area for arriving ambulances, personnel, EMS crash trucks and the EMS MCI unit early, a lesson learned in training and from past incidents.

Almost all units followed the directive to arrive at the scene by traveling south from Laskin Road. The few that did not, or could not, were delayed in traffic congestion.

During the quickly unfolding incident, multiple proper vehicle staging and positioning was critical, and leaving adequate space for ingress and egress of units was essential. Within a few minutes of arrival, Delp communicated by cell phone with the charge nurse at Sentara Virginia Beach General Hospital, the primary destination for the first patients. He provided a preliminary size up of the incident and a warning about potential mass casualties. This early alert provided ample opportunity for hospital administration to activate the hospital’s external disaster plan, mobilize its personnel, call in off-duty staff and prepare for the worst.

At this point, more units were beginning to arrive in rapid succession. When EMS Division Chief Ed Brazle (EMS-22) arrived, his collateral responsibility as the department’s emergency management coordinator helped define the forward triage area. Brazle directed the on-scene crews to bring stretchers and other specified equipment to the corner of Fleming and Birdneck and be ready to receive patients.

This was a good location for staging equipment and personnel because it allowed for rapid ingress and egress by crews in the event that a patient required a stretcher. In addition, there was a UPS store with a parking lot at that corner. The parking lot ultimately served as the location for command post tent for unified command. EMS officers participated in the unified command in key leadership positions, including area command, medical branch director and liaison officer.

Triage, treatment and transportation sector officers were also appointed early, and EMS area command director EMS-5 was advised. The system was gearing up for what was logically expected to be heavy casualties. Deputy EMS Chief William Kiley and Operations Medical Director Stewart Martin were now on scene.

After completing an initial scene walkaround, Brigade Chief Joseph Corley established a rehab location at the southeast corner of Fleming and Birdneck. He assigned a rehab officer and assisted in deploying equipment and personnel.

Within about 10 minutes of establishing that rehab location, the first wave of firefighters began to arrive after mounting the initial, aggressive fire attack and evacuations. The EMS team attended to them and documented each encounter as they awaited recall into the scene. This reinforces the need for rehab to be established and announced to all personnel as early as possible.

The initial incident commander followed the fire department’s pre-plan for the apartment complex and located the command post where the first-in district chief and battalion chiefs parked near the fire buildings with easy access through the parking lot from Birdneck Road.

However, one of the initial 5″ feeder hoses laid by the first-in apparatus, which caused problems for emergency vehicles and equipment by blocking access to several areas. After realizing this, fire crews enlisted the assistance of several citizens to help move the heavy hose and resolve the problem.

Some 45 minutes into the call, it was believed that few, if any, civilian injuries would be coming to the waiting triage teams. Thoughts then began to shift to establishing a temporary morgue because of the multiple buildings heavily engulfed in flames.

Expecting the Worst

The initial location selected for the morgue was on one of the side streets of the complex. This proved to be an inappropriate location because command wanted all bodies to be decontaminated before they were placed in body bags and delivered to the morgue. This is because of the significant presence of airborne carbon-fibers and fuel created by the burning plane and buildings. Therefore, fatalities couldn’t simply be bagged and transported.

Therefore, an alternative location that was more suitable for the decontamination operations was selected on a side street in front of the initial on-site morgue location. The plan called for the deceased to be brought to the decontamination area to be thoroughly decontaminated. They were then to be placed into a body bag with a second body bag over the first one to ensure any contaminants from the first bag were encased in the second.

It was initially believed that there would be a significant number of deceased as the building searches continued. Therefore, it was felt that the local medical examiner’s office wouldn’t be suitable because of its limited capacity.

During a subsequent discussion at the command post, the police commander decided that the anticipated volume of fatalities would be better staged at the Law Enforcement Training Academy (LETA) located less than a mile south on Birdneck Road. Commanders felt that facility would be more secure and private than the initial open location on the side street. LETA was readied as the collection point for any fatalities but wasn’t actually used for its converted purpose because no fatalities were discovered.

Personnel Accountability

One issue that arose at the scene was the proper accountability of personnel. Many volunteers and other first responders self dispatched to the scene. Some didn’t have proper identification and some weren’t appropriately dressed.

Identification became an issue because law enforcement officers who were under orders to allow only authorized personnel into the area began to refuse access for some.

The decision was made to announce over radio systems and other communication means that enough personnel were available at the site and no additional personnel were needed.

In addition, for the purpose of uniformity and security, law enforcement personnel were advised that any member claiming to be with EMS who failed to present proper identification was to be turned away. Although some were unhappy they weren’t allowed to become a part of “the big one,” restricting access to only those with proper identification was for the best.

Personnel management issues stemmed from having so many members on scene and still arriving with no assignments, coupled with a lack of patients. To solve the personnel management issues, Virginia Beach Volunteer Rescue Squad Chief Roy White, Jr. was assigned to manage the EMS personnel. Within 15 minutes, White established a meeting place for all on-scene and arriving personnel, assigned an assistant and got EMS personnel accountability under control.

Accountability and identification wasn’t limited to first responders. Support personnel, such as utility workers and civilian contractors called in by the Navy, also didn’t always have proper identification. This posed a challenge for the incident liaison officer, EMS Division Chief Tom Green, who was responsible for their accountability.

At large-scale incidents such as this, personnel management and accountability needs to be established early in the incident to account for and manage responding on-duty and off-duty staff, as well as contracted or requested support personnel. Incoming first responders and activated support personnel need to be advised of the scene’s restricted access and that proper identification will be required. The maximum number of EMS personnel needed at the scene must be determined early in the incident—with overflow personnel advised to report to a rescue station. This will better control on scene and back-up resources and ensure the availability of relief personnel should extended operations be needed.

The Media Rush

From the moment the incident was a confirmed plane crash and, more specifically, a Navy F/A-18 fighter jet crash, incident managers knew it was going to be a huge media event.

Although it’s important to get the news out, it’s more important to get correct information out. Rumors and misinformation often run rampant during large incidents, and this case was no different.

A media staging area was established early on in the parking lot at 24th Street and Birdneck Road. Initially, that designation actually meant little or nothing to the reporters who wanted video of the fire and interviews with patients, residents and first responders.

Initially, no one was available or assigned to corral and monitor the media location. It took a while, but the scene became better defined, taped off and organized. Once enough law enforcement and military police were on scene, this area became well organized, and personnel from the media were redirected and briefed there. This also became the established site for several formal news conferences.

Within two hours of the incident, the city’s Media and Communications Group, a component of the city manager’s office, established a modified joint information center at the city’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) and began to disseminate the information to the public via social media and standard news releases.

Inquiries from dozens of media outlets from several countries flooded the 311 information center and EOC in during the first eight hours at an out-of-control pace. The incident was big news, initially because of the military link, and it grew even bigger as it became more and more apparent that there were no fatalities and only a handful of minor injuries. The news media began to play up the “miracle” aspect of such a large event.

Priority Cell Phone & VoIP Access

Verizon Wireless is the wireless provider for the city of Virginia Beach. It’s also a major Virginia wireless provider. With the crush of citizen cell phone use (for voice and data), the wireless towers quickly became overloaded, and many calls were not able to go through. This hindered operations for police, fire, EMS and other agencies at the scene and created a level of frustration among providers that needs to be addressed for future incidents.

At a post-incident discussion with a representative of a of Verizon Wireless of Southeastern Virginia, VBDEMS learned about Verizon’s emergency wireless public access (WPA) system, which allows authorized emergency responders to have priority access to cell phone sites. That priority service is part of post-9/11 legislation to improve first responder communications during emergencies. It relies on local jurisdictions to determine the users and policies.

Although WPA may sound like a solution, it also has its limitations. Regardless of the carrier, only a specific capacity can be used, and when that capacity reaches its maximum, no other access is possible. A better alternative is to use push-to-talk or other technologies, such as texting or tweeting on a pre-established emergency Twitter account. Each uses voice over Internet protocol (VoIP) and sends digital “packets” in a way that allows far more users to access it at once.

It was also learned through a post-incident review that although the user of a cell phone may feel as though their call didn’t go through, it’s possible that the individual’s call was in a “queue” and would have eventually connected when a wireless cell became available. Despite this knowledge, first responders will not hold on indefinitely without any indication as to when the call will ultimately connect. The lesson learned from this is that VoIP alternatives need to be established and practiced before a major incident occurs.

Lessons Learned

1. Scene tape should be deployed, and policed, as early as possible into a major incident. This will establish and maintain a large, controlled scene perimeter and ensure security for personnel, patients and their assets.

2. The onslaught of media attention is often too much for the one agency’s public information officer (PIO) to handle, so a coordinated approach should be established early into an incident by all of the public safety PIOs and the city media communications manager (MCG ).

3. Use of established social media communications is often effective and should be explored.

4. Multiple news releases; frequent, scheduled and announced media updates; and traffic message signs on the interstate roads should be used.

Conclusion

The F/A-18 fighter jet crash into Mayfair Mews Apartments tested the Virginia Beach emergency resources in many ways. But the years of training and MCI drills among all public safety agencies and regional military, plus the use of a unified incident command system, proved invaluable.

MCI drills typically concentrate on handling a wide array of injuries and numerous fatalities. They focus on using proper triage methods and triage tags. They establish working models for successful unified command, branches and divisions to effectively triage, treat and distribute patients among all area hospitals.

It was difficult to believe that both pilots could eject from the jet seconds before it hit the ground and have only relatively minor injuries; by the time this fact was discovered, the first-due ladder trucks, engines and a district chief had arrived and confirmed multiple apartment buildings heavily engulfed in fire as a result of the plane crash.

What MCI drills don’t usually focus on is the type of multi-building incident that requires massive logistics, resources and personnel deployment to be involved in extended search-and-rescue operations, evacuations and the establishment of multiple triage posts around an occupied apartment complex, only to have no fatalities and very few minor injuries.

Much was learned by the incident managers and crews in Virginia Beach. The advanced training and use of unified command on a routine basis helped the agencies in their response, command and control operations and on-scene actions. All involved believe the lessons learned from this case will help the Virginia Beach emergency response system grow and improve so that it can operate in an even better manner at future incidents of this magnitude.

About the Authors

Bruce Nedelka, NREMT-P, is a division chief and department public information officer for VBEMS. He can be contacted at BNedelka@vbgov.com.

A.J. Heightman, MPA, EMT-P, is the editor-in-chief of JEMS and a recognized mass casualty incident management educator. Contact him at a.j.heightman@elsevier.com.

Adapted and reprinted from July 2012 JEMS with the permission of Elsevier Public Safety.